Climate change: obsession with plastic pollution distracts attention from bigger environmental challenges

By now, most of us have heard that the use of plastics is a big issue for the environment. Partly fuelled by the success of the BBC’s Blue Planet II series, people are more aware than ever before about the dangers to wildlife caused by plastic pollution – as well as the impact it can have on human health – with industries promising money to tackle the issue.

Single use plastics are now high on the agenda – with many people trying to do their bit to reduce usage. But what if all of this just provides a convenient distraction from some of the more serious environmental issues? In our new article in the journal Marine Policy we argue plastic pollution – or more accurately the response of governments and industry to addressing plastic pollution – provides a “convenient truth” that distracts from addressing the real environmental threats such as climate change.

Yes, we know plastic can entangle birds, fish and marine mammals – which can starve after filling their stomachs with plastics, and yet there are no conclusive studies on population level effects of plastic pollution. Studies on the toxicity effects, especially to humans are often overplayed. Research shows for example, that plastic is not as great a threat to oceans as climate change or over-fishing.

Read more: Plastics in oceans are mounting, but evidence on harm is surprisingly weak

More easily fixed?

Taking a stand against plastic – by carrying reusable coffee cups, or eating in restaurant chains where only paper straws are provided – is the classic neoliberal response. Consumers drive markets, and consumer choices will therefore create change in the industry.

Alternative products can often have different, but equally severe environmental problems. And the benefits of these small-scale consumer driven changes are often minor. Take, for example, energy-efficient light bulbs – in practice, using these has been shown to have very little effect on a person’s overall carbon footprint.

But by making these small changes, plastic still appears to be an issue we can address. The Ocean Cleanup of plastic pollution – which aims to sieve plastic out of the sea – is a classic example. Despite many scientists’ misgivings about the project and its recent failed attempts to collect plastic the project is still attractive to many as it allows us to tackle the issue without having to make any major lifestyle changes.

The real issue

That’s not to say plastic pollution isn’t a problem, rather there are much bigger problems facing the world we live in – specifically climate change.

In October last year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produced a report detailing drastic action needed to limit global warming to 1.5˚C. Much of the news focused on what individuals could do to reduce their carbon footprint – although some articles did also indicate the need for collective action.

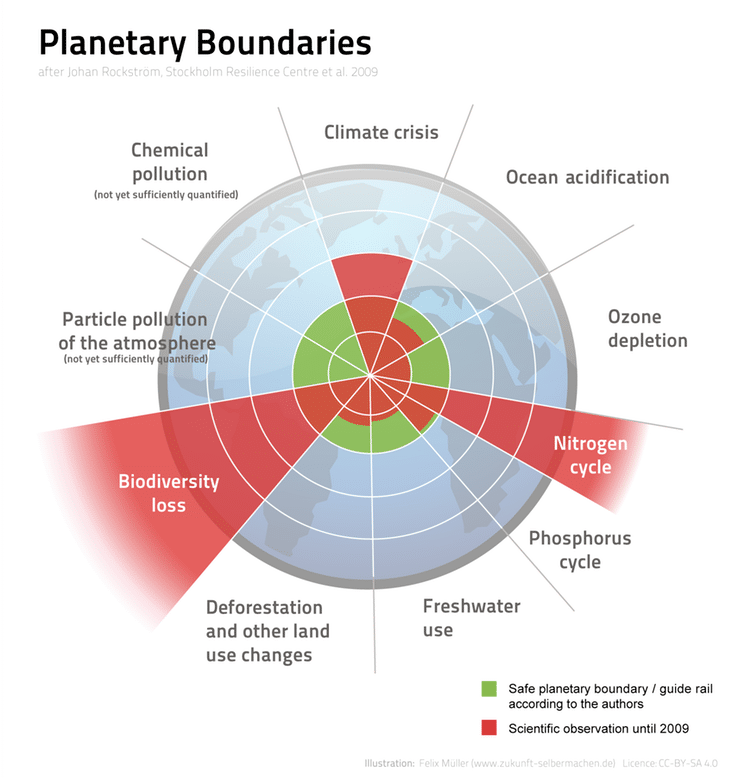

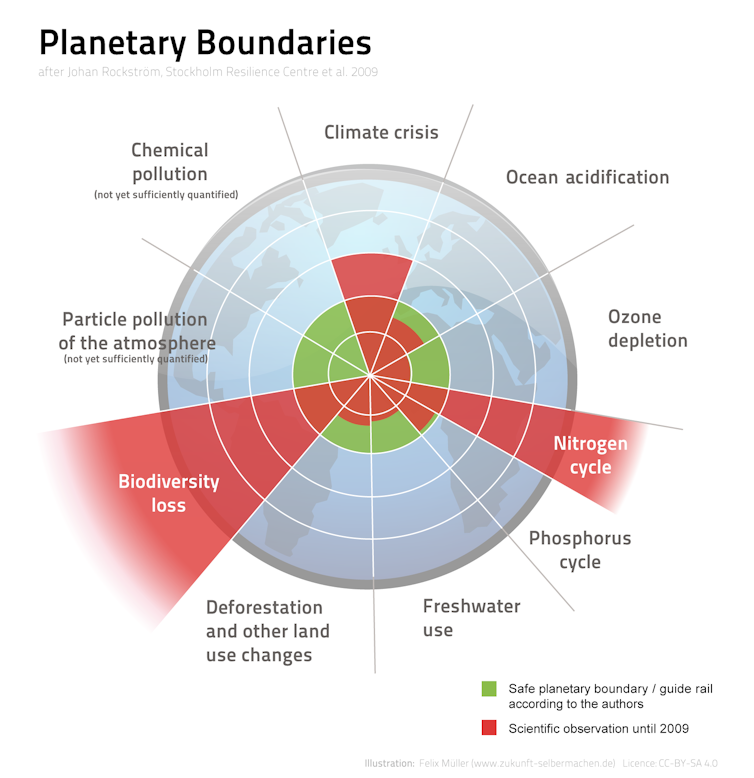

Despite the importance of this message, environmental news has been dominated by the issues of plastic pollution. So it’s not surprising that so many people think ocean plastics are the most serious environmental threat to the planet. But this is not the case. In 2009 the concept of planetary boundaries was introduced to indicate safe operating limits for the Earth from a number of environmental threats.

Three boundaries were shown to be exceeded: biodiversity loss, nitrogen flows and climate change. Climate change and biodiversity loss are also considered core planetary boundaries meaning if they are exceeded for a prolonged time, they can shift the planet into new, less hospitable, stable states.

These “clear and present dangers” of climate change and biodiversity loss could undermine the capacity of our planet to support over seven billion people – with the loss of homes, food sources and livelihoods. It could lead to major disruptions of our ways of life – by making many areas uninhabitable due increased temperatures and rising sea levels. These changes could start to happen within the current century.

Lifestyle overhaul

This is not to distract from the fact that some significant steps have been taken to help the planet environmentally by reducing plastic waste. But it is important not to forget the need for large-scale systemic changes needed internationally to tackle all environmental concerns. This includes longer-term and more effective solutions to the plastic problem – but also extending to more radical large-scale initiatives to reduce consumption, decarbonise economies and move beyond materialism as the basis for our well-being.

The focus needs to be on making the way we live more sustainable by questioning our overly consumerist lifestyles that are at the root of major challenges such as climate change, rather than a narrower focus on sustainable consumer choices – such as buying our takeaway coffee in a reusable cup. We must reform the way we live rather than tweak the choices we make.

There is a narrow window of opportunity to address the critical challenge of, in particular, climate change. And failure to do so could lead to massive systemic impacts to the Earth’s capacity to support life – particularly the human race. Now is not the time to be distracted by the convenient truth of plastic pollution, as the relatively minor threats this poses are eclipsed by the global systemic threats of climate change.

Rick Stafford, Professor of Marine Biology and Conservation, Bournemouth University and Peter JS Jones, Reader in Environmental Governance, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.