Plastic bag bans can backfire if consumers just use other plastics instead

Governments are increasingly banning the use of plastic products, such as carryout bags, straws, utensils and microbeads. The goal is to reduce the amount of plastic going into landfills and waterways. And the logic is that banning something should make it less abundant.

However, this logic falls short if people actually reuse those items instead of buying new ones. For example, so-called “single-use” plastic carryout bags can have a multitude of unseen second lives – as trash bin liners, dog poop bags and storage receptacles.

A U.K. government study calculated that a shopper would need to reuse a cotton carryout bag 131 times to reduce its global warming potential – its expected total contribution to climate change – below that of plastic carryout bags used once to carry newly purchased goods. To have less impact on the climate than plastic carryout bags also reused as trash bags, consumers would need to use the cotton bag 327 times.

My research has evaluated carryout bag regulations from many angles. In a recent study, I examined how plastic carryout bag bans in California have changed the types of bags people use at checkout, as well as these bans’ unintended impacts on consumer purchasing habits. My results showed that bag bans may not reduce total plastic usage if people begin purchasing trash bags to replace the carryout bags they were previously reusing for their garbage. As this finding shows, well-intended product bans can have unintended consequences.

Plastic bag use in California

California provides a unique laboratory for studying plastic bag regulations. From 2007 through 2015, 139 California cities and counties implemented plastic carryout bag bans. This local momentum led to the first statewide plastic bag ban in the United States, voted into law on Nov. 8, 2016. Because these restrictions were adopted at different times across the state, I was able to compare bag usage at stores with bans to those without, while also accounting for potentially confounding factors, such as seasonal shopping patterns.

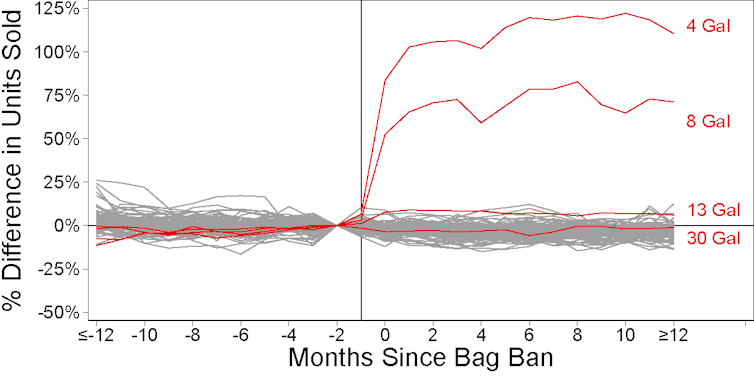

Using sales data from retail outlets, I found that bag bans in California reduced plastic carryout bag usage by 40 million pounds per year, but that this reduction was offset by a 12 million pound annual increase in trash bag sales. This meant that 30 percent of the plastic eliminated by the ban was coming back in the form of trash bags, which are thicker than typical plastic carryout bags.

In particular, my results showed that bag bans caused sales of small (4 gallon), medium (8 gallon) and large (13 gallon) trash bags to increase by 120 percent, 64 percent and 6 percent respectively.

Disposable does not automatically mean single-use

Although plastic carryout bags are widely referred to as “single-use,” consumers don’t necessarily treat them that way. By comparing the reduction in plastic carryout bags used at checkout to the increase in trash bags sold, my results revealed that 12 to 22 percent of plastic carryout bags were reused in California as trash bags pre-ban. Each reuse avoided the manufacture and purchase of another plastic bag.

Moreover, my study underestimated reuse because it did not examine other ways in which people use plastic carryout bags, such as wrapping fragile items for shipping or storage instead of using plastic bubble wrap. Nor did it address increased use of reusable bags made of thicker plastic in place of disposable plastic bags.

The U.K. study did examine the impact of shifting to thicker reusable plastic bags. It found that if these thicker bags were not reused between 9 and 26 times, they would have a higher global warming potential than disposable plastic carryout bags reused as trash bags.

Who bears the burden?

Who were the people who reused plastic carryout bags pre-ban, and presumably bore the burden of buying trash bags post-ban? I found that bag reuse was higher for people who purchased pet items and baby items – in other words, who needed to collect and dispose of excrement. In 2017, nearly 6 percent of U.S. households had a child under 5 years old, 44 percent owned a dog, and 35 percent owned a cat.

I also found that plastic bag reuse was higher among people who shopped for bargains. Although reusing shopping bags as trash bags could be motivated by environmental concern, it also could be motivated by frugality. Interestingly, I did not find a correlation between plastic bag reuse and income or political leaning, but I did find a positive correlation with higher levels of education.

The case for fees instead of bans

Why didn’t policymakers foresee that bag bans could drive up trash bag sales? Policies typically miss the mark because policymakers either do not understand people’s current behavior or fail to anticipate how people will respond in a completely new situation.

Banning carryout bags illustrates the first problem. Before plastic bags were banned, there was little data on who reused plastic bags or how they reused them. California’s natural experiment revealed this information for other jurisdictions to improve upon.

In my view, policymakers who want to minimize plastic use should consider ways to help people who want to reuse disposable bags. One option would be to offer incentives for producing inexpensive, thin carryout bags specifically designed and marketed to be used first as carryout bags, then for trash. Such bags would need to sell for less than 9 cents per bag to be price-competitive with current 4-gallon trash bags. Ideally, they would be thin enough to contribute no more to climate change than traditional carryout bags.

Another route that some jurisdictions, including Washington, D.C., have implemented is adopting plastic bag fees instead of bans. This approach, which allows customers to continue using plastic carryout bags as trash bags for a small fee, has been shown to be as effective as bans in encouraging consumers to switch to reusable bags.

However, current bag fees have not promoted other uses for disposable carryout bags. These policies could be improved by educating customers about the environmental benefits of reusing disposable products. As a general rule, the more an object can be reused – even a disposable item – the better for the environment.

Rebecca Taylor, Lecturer in Economics, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.