There's no 'garbage patch' in the Southern Indian Ocean, so where does all the rubbish go?

Great areas of our rubbish are known to form in parts of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. But no such “garbage patch” has been found in the Southern Indian Ocean.

Our research – published recently in Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans – looked at why that’s the case, and what happens to the rubbish that gets dumped in this particular area.

Every year, up to 15 million tonnes of plastic waste is estimated to make its way into the ocean through coastlines (about 12.5 million tonnes) and rivers (about 2.5 million tonnes). This amount is expected to double by 2025.

Read more: A current affair: the movement of ocean waters around Australia

Some of this waste sinks in the ocean, some is washed up on beaches, and some floats on the ocean surface, transported by currents.

The garbage patches

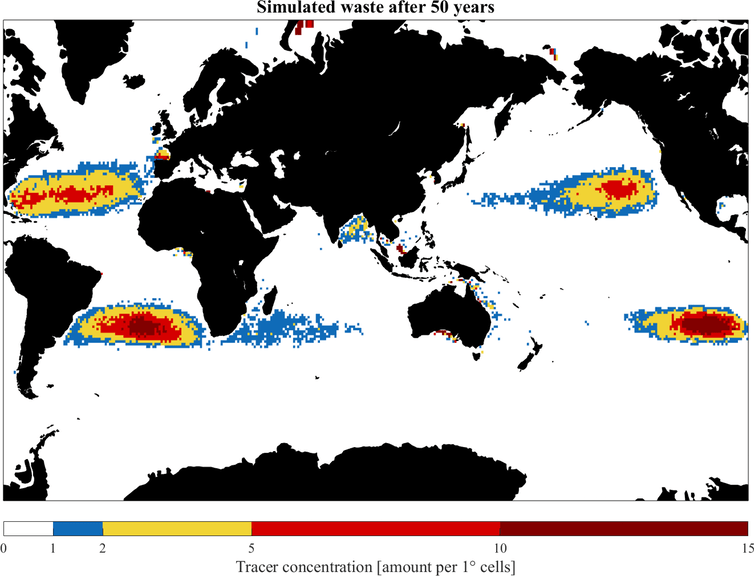

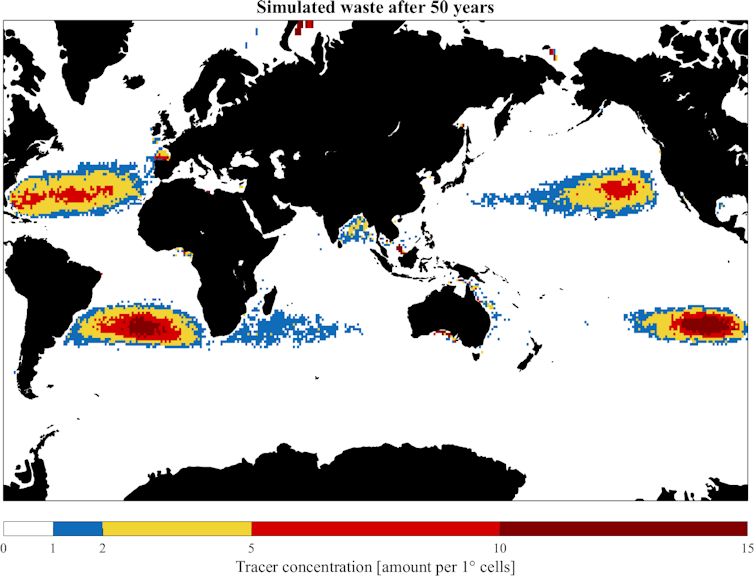

As plastic materials are extremely durable, floating plastic waste can travel great distances in the ocean. Some floating plastics collect in the centre of subtropical circulating currents known as gyres, between 20 to 40 degrees north and south, to create these garbage patches.

Here, the ocean currents converge at the centre of the gyre and sink. But the floating plastic material remains at the surface, allowing it to concentrate in these regions.

The best known of these garbage patches is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which contains about 80,000 tonnes of plastic waste. As the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration points out, the “patches” are not actually clumped collections of easy-to-see debris, but concentrations of litter (mostly small pieces of floating plastic).

Similar, but smaller, patches exist in the North and South Atlantic Oceans and the South Pacific Ocean. In total, it is estimated that only 1% of all plastic waste that enters the ocean is trapped in the garbage patches. It is still a mystery what happens to the remaining 99% of plastic waste that has entered the ocean.

Rubbish in the Indian Ocean

Even less is known about what happens to plastic in the Indian Ocean, although it receives the largest input of plastic material globally.

For example, it has been estimated that up to 90% of the global riverine input of plastic waste originates from Asia. The input of plastics to the Southern Indian Ocean is mainly through Indonesia. The Australian contribution is small.

The Indian Ocean has many unique characteristics compared with the other ocean basins. The most striking factor is the presence of the Asian continental landmass, which results in the absence of a northern ocean basin and generates monsoon winds.

As a result of the former, there is no gyre in the Northern Indian Ocean, and so there is no garbage patch. The latter results in reversing ocean surface currents.

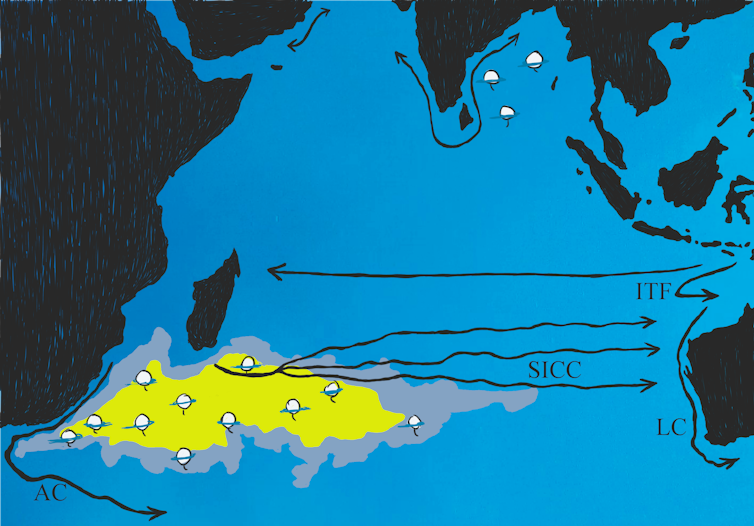

The Indian and Pacific Oceans are connected through the Indonesian Archipelago, which allows for warmer, less salty water to be transported from the Pacific to the Indian via a phenomenon called the Indonesian Throughflow (see graphic, below).

This connection also results in the formation of the Leeuwin Current, a poleward (towards the South Pole) current that flows alongside Australia’s west coast.

As a result, the Southern Indian Ocean has poleward currents on both eastern and western margins of the ocean basin.

Also, the South Indian Counter Current flows eastwards across the entire width of the Southern Indian Ocean, through the centre of the subtropical gyre, from the southern tip of Madagascar to Australia.

The African continent ends at around 35 degrees south, which provides a connection between the southern Indian and Atlantic Oceans.

How to follow that rubbish

In contrast to other ocean basins, the Indian Ocean is under-sampled, with only a few measurements of plastic material available. As technology to remotely track plastics does not yet exist, we need to use indirect ways to determine the fate of plastic in the Indian Ocean.

We used information from more than 22,000 satellite-tracked surface drifting buoys that have been released all over the world’s oceans since 1979. This allowed us to simulate pathways of plastic waste globally, with an emphasis on the Indian Ocean.

We found that unique characteristics of the Southern Indian Ocean transport floating plastics towards the ocean’s western side, where it leaks past South Africa into the South Atlantic Ocean.

Because of the Asian monsoon system, the southeast trade winds in the Southern Indian Ocean are stronger than the trade winds in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. These strong winds push floating plastic material further to the west in the Southern Indian Ocean than they do in the other oceans.

So the rubbish goes where?

This allows the floating plastic to leak more readily from the Southern Indian Ocean into the South Atlantic Ocean. All these factors contribute to an ill-defined garbage patch in the Southern Indian Ocean.

In the Northern Indian Ocean our simulations showed there may be an accumulation of waste in the Bay of Bengal.

Read more: 'Missing plastic' in the oceans can be found below the surface

It is also likely that floating plastics will ultimately end up on beaches all around the Indian Ocean, transported by the reversing monsoon winds and currents. Which beaches will be most heavily affected is still unclear, and will probably depend on the monsoon season.

Our study shows that the atmospheric and oceanic attributes of the Indian Ocean are different to other ocean basins and that there may not be a concentrated garbage patch. Therefore the mystery of all the missing plastic is even greater in the Indian Ocean.

Mirjam van der Mheen, PhD Candidate in Oceanography, University of Western Australia; Charitha Pattiaratchi, Professor of Coastal Oceanography, University of Western Australia, and Erik van Sebille, Associate Professor in Oceanography and Climate Change, Utrecht University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.