Table of Contents

Oysters filter water, they have a remarkable ability to filter nitrogen pollution from water as they eat. Research conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)[1] found water to be clearer and healthier in areas with restored oyster reefs that contained high oyster density. This capacity is being adopted by projects worldwide for the general restoration of natural habitats or to improve water quality, like in Chesapeake Bay Program[2] or Florida Oyster Cultch Placement Project.[3] The best known of these projects is the billion oyster project in New York[4] with the declared goal of having one billion living oysters in New York waters by 2035. By mid-2019, more than 28 million oysters were distributed.

The billion oyster project in New York inspired us!

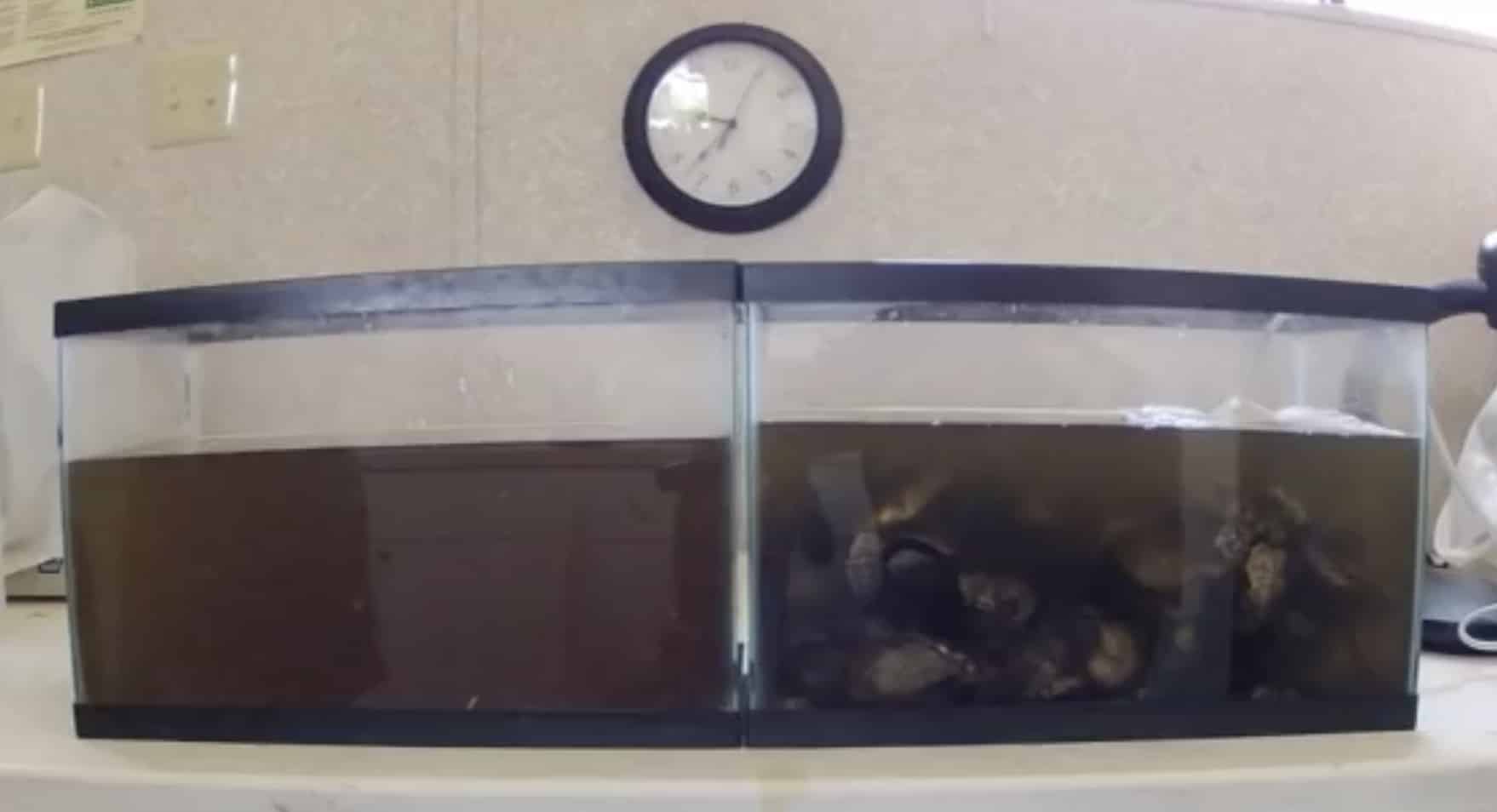

Image Comparison: The Power of the Oyster -> Cleaning Capacity

With our project at the CMU we want to prove that our oysters in Jamaica are also able to filter water and improve water quality. There is an urgent need to enhance the overall quality of Kingston Harbor. Oyster can be a part of that fantastic idea to restore the Kingston Harbor to its former glory.

Jamaica has some experience with commercial oyster farming (International Development Research Centre, 1992).[5] Oyster culture began in 1977 with studies to assess feasibility (Wade et al. 1981).[6] Unfortunately, from all the promising projects launched at UWI in the 1990s with international support, only one remains; the oyster farm in Bowden Bay, an area that had high density of mangrove oyster (Crassostrea rhizophorae).

Bowden Oyster Farm in Jamaica

[1] NOAA COASTAL OCEAN PROGRAM (2005). Science-based Restoration Monitoring of coastal habitats. Decision Analysis Series No. 23, Volume

[2] https://www.chesapeakebay.net/issues/oysters

[3] https://pub-data.diver.orr.noaa.gov/restoration/NRDA%20FL%20Oyster%20Cultch%20Monitoring%20Report%202017

[4] https://billionoysterproject.org/

[5] International Development Research Centre (1992): 101 technologies from the South for the South. Section 34: Artisanal oyster farming.

[6] Wade, B & Brown, R & Hanson, C & Alexander, L & Hubbard, R & Lopez, B. (1981). The development of a low technology oysterculture industry in Jamaica. Gulf Caribb. Fish. Inst., Univ. Miami, Proc., 33rd. 6-18.

Aspects of the project

That project, like others were focused on the economic aspect, to make money out of it and to provide a new employment option. The initial technology was adapted from Cuban techniques (Wade et al. 1981).[1]The small industry came to an end because it suffered from pollution and theft.

As recommended by some researchers (e.g. Coen and Luckenbach 2000),[2] we clearly define our objectives in order to differentiate between the introduction of aquaculture and the ecological restoration of ecosystems.

Our project has three different aspects/phases.

- Ecological: -> Cleaning water/filtering water. Improving the quality of water in Kingston Harbor by making use of Oyster power. Securing and maintaining the cleaned waters within the Kingston Harbor for cultivating edible commercial oysters in a later phase.

- Educational: -> Training/Education in aquaculture technology, Learning sites for Blue Economy, Ocean Awareness through partnership/stewardship of part of the project to put students at the center of the movement to restore oysters.

- Economical: -> Providing edible raw oysters for realizing a practical case of “Blue Economy”. Oysterfarm/Aquaculture for the national market and as a alternative source of income for the fisherfolk.

[1] Wade, B & Brown, R & Hanson, C & Alexander, L & Hubbard, R & Lopez, B. (1981). The development of a low technology oysterculture industry in Jamaica. Gulf Caribb. Fish. Inst., Univ. Miami, Proc., 33rd. 6-18.

[2] Coen, L. D. and M. W Luckenbach (2000). Developing success criteria and goals for evaluating oyster reefrostoration: Ecological function or resource exploitation? Ecological Engineering 15:323-343.

Caribbean Maritime University

The Caribbean Maritime University (CMU) is the largest regional maritime university conducting applied research in maritime and marine biotechnology and therefore has a powerful practical orientation.

Photo: Aerial View of the CMU (has to be updated with FACT Centre)

The University has the materials and personnel for building, maintaining and operating UAV and UUV robotics for harbor cleaning as well as sufficient space for growth and proliferation of oysters at different sitThe institution has the capacity and pertinent resource for the building of artificial coral reefs and the replanting of mangroves along the Palisadoes corridor.

The challenges are vast, the first being the convincing of persons about the benefit of this project to prevent removal of larvae from particular sites. Education and economic benefits are paramount in this case. Creating a relationship with those from the area and surrounding communities could solve this.

We have a conviction that the Kingston Harbor has a feasibility of creating and developing the eco-tourism industry.

There is a big mangrove lagoon in Port Royal where we can see fish jumping and pelicans dive. It is also home to crocodiles.

Port Royal as part of this protected area including aspects of the harbor is a historical town that was famous for Caribbean Pirates in the distant past, historic ruins of huge fortress, earthquake disaster in 1692 and so on. The remains are still there – the so-called Sunken City.

We have a calm and spacious harbor, where we used to enjoy swimming, fishing, yacht sailing and cruising. There used to be a big swimming tournament across the harbor.

Photo: Recreational use of the Kingston Harbor

Turning our eyes to the outside of the harbor, there spreads a world of rich coral reefs. There is, for instance, a fantastic coral island “Lime Cay”, where we can enjoy swimming, diving, fishing and sun-bathing on the beautiful white sand.

The main campus of the CMU is located on the Palisadoes sandbar. We can find some small lagoons neighboring the CMU campus, where abundant flora and fauna can be observed.

The Palisadoes sandbar already has hotels, restaurants and a yacht club. In addition, there is the UWI (University of the West Indies) marine research institute. NEPA (National Environment and Planning Agency), NWA (National Works Agency) and UWI’s co-operation have already been engaged in the mangrove tree re-planting project for shore protection works.

We believe that it is possible for us to create a major eco-tourism in this area through the cooperation of these resources and related authorities. The first step we need is to improve the environmental conditions in Kingston Harbor. For that ecological purpose, we plan to make use of Oyster Power in filtering and purifying seawater quality.

The second (economic) phase is to re-establish the oysters as an aquaculture project. There is not a single aquaculture project in the Kingston area or inside the Palisadoes/Port Royal Protected Area. The small-scale fisher folks catch fish in this polluted harbor and the surrounding areas. This not only poses threat to health, but it also has an impact on the socio-economic aspect where regulation of income in this protected area especially is concerned. There are little to no convincing incentives for fisherfolk to respect the protected area.

There are three stages in the project, namely:

- Incorporating the project into the educational activities here at the University

- Inviting partners and stakeholders to become part of this collective effort

- Seeking and realizing a practical case of the Blue Economy

With these partners, provisions of field-based science lessons through the experience of oyster farming and ultimately an ecosystem restoration will be had. We wish to identify a practical case for the Blue Economy by ecosystem restoration which was adapted from New York’s One Billion Oyster Project.

Kingston Harbor

The Kingston Harbor being one of the most viable, economically and environmentally is an undermined treasure to Kingston and by extension the entire country. Given its state in recent years owing to the amount of waste emptied in its waters by way of 19 gullies, surrounding factories and marine vessels, time is of the essence that we address it before it becomes an irreversible nightmare. There was a time when Jamaicans could enjoy a swimming competition across the harbor from Gun Boat Beach to Victoria Pier, formerly Orange Street. This is not so at this time, it is so polluted that it is advised that no one should swim in its waters. After a downpour the Kingston Harbor is filled with debris, from marine plastics to old refrigerators, most waste being plastic bottles.

Oyster breeding season begins in May and continues to November; therefore, the main breeding periods are May through June and October through November which are the main rainy seasons in Jamaica. This works well for oyster breeding since decreased sea salinity encourages/increases successful breeding periods.

- Nursery designing

The following components take into consideration that the breeding season of these oysters begins semi-annually in May and November each year. We would have identified the places to farm these oysters and identified estuaries for collecting the oyster larvae. We identified in May two possible sites between the Norman Manley International Airport and Port Royal.

The first component entails designing and crafting the nursery environment for the collection of larvae with the use of durable mesh/net bag or crates where the nursery is placed.

Second component includes collecting the oyster larvae from the estuaries and transplanting unto different substrates/mediums such as coconut shells, dead tree branches etc.

We started end of May with the placement of crates in Rosey Hole, close to Port Royal. We are using plastic containers, which are each separately filled with coconut shells, conch shells, and oyster shells. We also are using strings with pieces of tires hanging down from a jetty in Rosey Hole.

Collecting of oyster larvae and transfer to an area close to the campus.

Larvae growth observation

Water quality research before and after transfer of oysters

Collection of oyster larvae and transfer for second phase and growth observation

Harvesting of oysters firstly for extending the Harbor Restoration Project

Transfer of know-how/concepts, the technology will be used as modules for other parts of the island in cooperation with the fishing community.

The aim of the project is to use oysters for improving water quality. The Flat Oyster which is present in abundance at our current breeding site, can filter and clean water up to 135 liters per day per oyster. These natural filter crustaceans can clean polluted water with proven evidence, as it has been tested and tried for harbors outside of Jamaica.

Third seeks to transplant these larvae at specifically identified areas (shallow areas along the shore) by the Kingston Harbor. Data will be recorded at this stage for future reference in comparing data for results. Temperature, pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO) and COD are the items observed.

Lessons Learned

Being our first major project in this regard, any learning moment would have been experienced during the project as well as through others’ experiences.

In the past, there has been aims at having similar projects successful, however theft has caused a pause on such. We have learnt from these experiences and have sought to, through corporation with fisherfolks, approach this project from a different angle. This we believe will be most beneficial for all involved.

Briefly outline technical parameters, analysis of alternatives.

Our final goal is to improve the water quality for harbor restoration.

Long term plans require edible fresh oysters and must be grown and harvested within the clean water site.

Current status of water quality in the Port Royal mangrove area, Kingston Harbor is as follows.

According to the water quality data in the Port Royal mangrove area (2 spots) conducted in May of 2019:

- ◆ Temperature; 30.2℃ & 31.2℃

- ◆ DO; 6mg/L for the 2 spots

- ◆ Salinity; 37 & 35

DO and Salinity are acceptable, but temperature is little bit high which is likely difficult for oysters to grow big. And it is hard for us to manage the temperature because of climate change and global warming, a pressing global issue.

The causes of the harbor pollution is derived from various kinds of inflows from the capital city Kingston, such as sewage, garbage, agricultural, industrial chemicals etc.

For our project, measures to reduce pollution sources should be taken simultaneously. That’s why close collaboration with related organizations will be inevitably required.

However, we can estimate the value of the sale of a part of the oyster production (specifically grown for this purpose) based on the selling price of oysters in the fishing village of Hellshire, in St. Catherine. The educational return will be an increase of awareness regarding the importance of a protected marine environment as an example of the growing importance of the Blue Economy. This also mirrors, in the long term, the impact inevitable natural disasters will have on Jamaica, as a small island developing state. The more prepared we are as a nation to cushion losses (which will be lessened based on the health of our coral reefs, mangroves and other marine interests), the less infrastructural and environmental damage will result, putting less strain on the country economically.

Main Risks and their Mitigating Factors

Risks to be expected are as follows:

➊ Effects of materials used for nursery reefs on the marine environment.

The impact of the seedling reefs on the environment is significant and so environmentally friendly materials need to be used. We have used shellfish’s shells, coconut shells, broken ceramics, dead trees and so on, which are all environmentally friendly.

➋ Effects of remarkable breeding of oysters on the marine environment.

When oyster’s excrements and carcasses are deposited on the seabed, harmful gases such as hydrogen sulfide may be generated. The proper procedures used to breed oysters will eliminate all risks due to improper breeding that may cause environmental pollution. Constant observation must be carried out.

➌ Food poisoning caused by theft and sale of oysters.

Since there is a high possibility of oyster contamination with polluted water, consumption is not recommended. This is where the surveillance and constant monitoring of these oyster reefs is implemented.

Our main aim is to improve the environment of the harbor and ensure balance for the environmental and social aspect.

From that perspective, we must continuously observe environmental parameters and make an effort to comply with the NEPA’s environmental standards.

CMU is a member of the management committee of the PPRPAC. There is a socio-economic risk where the fishing community might not understand the importance of the Protected Aera. The oyster farm faces the risk of theft and destruction because a quick win could look more attractive than sustainability.

To minimize these risks, it is crucially important to convince the fisherfolks about the importance of the project. The sustainable success of the project needs the help and engagement for the fishing community, a deeper understanding of the purpose of a Protected Area to realize that is for their long-term economic benefit.

To minimize the risk of theft, the oyster farm will be protected with advanced technology. The proximity of the oyster nursery and farming installation to the University will also reduce the risk of theft.

Project partners (potential and otherwise):

We seek to partner with organizations and fisherfolk to ensure the success of this project. Several organizations such as the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Agriculture and Fisheries (MICAF), the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA), the University of West Indies (UWI), NGO’s like iAspire and others will be engaged.

We plan to do regular observation activities in cooperation with those who become members of the project.

The following are the strengths of each potential partner:

➊ MICAF; Taking advantage of the experience of oyster farms over many years in the Bowden Bay Oyster Farm, MICAF plays a leading role in the technical field of oyster cultivation.

➋ NEPA; Taking advantage of its expertise of marine environmental research, NEPA takes a leading role in the evaluation of water quality, especially in environmental assessment from a broader perspective.

➌ UWI; Taking advantage of its expertise of marine environmental research, UWI takes a leading role in the water quality environmental survey.

➍ CMU through the Centre for Blue Economy and Innovation; the project’s secretariat will be set up at CMU to oversee the project and coordinate the entire activities and summarize opinions of the project team. The CMU also plays a role in promoting public relation activities widely in the society. The Centre for Blue Economy and Innovation at the CMU would have already made preliminary tests of water quality beneficial for initial stages in the rearing of oysters. In end of June 2019 we started collecting oyster larvae’s.

❺ Community Fisherfolk; this set of people are very important for the success of this project. Engaging them and encouraging partnerships will ensure that sites aren’t disturbed for economic gain given the risks to health if oysters from this site are ingested.

Economic gain on their side is also a concern, hence the idea of setting up a separate breeding site for suitable/edible oysters for the market.

A Project Meeting will be held regularly to ensure that the team’s consensus will be formed to promote the challenge successfully. The idea of scaling will also be dependent on these group of partners after further discussion.

Summary:

We will make use of ecosystem, rather than try to control nature. Restoring natural ecosystems and trusting its inherent power is one way. This is the main concept of the project.

The work is very simple, where we collect oyster larvae at the natural habitats of oysters and transplant them into the Kingston Harbor. We do not artificially breed oysters, nor do we feed them.

Consequently, marine grasses and planktons will grow and supply food to other creatures. Soon, bigger fish will come together for feeding and finally new fishing ground will be formed.

Thus, we aim to establish a mechanism for the expansion and re-production of the ecosystem.

We have a plan that this project will be incorporated into not only the CMU curriculum but also high schools’ curriculum across the country, and we hope it will enlighten the ideals of blue economy to the generation that bears the future.

The restoration of the environment of Kingston Harbor which borrows the power of oyster would not only embark upon an oyster business in the long term, but also lend that safety for seafood harvesting for those who rely on it for an income.

History of oyster culture in Jamaica

Oyster culture began in 1977 with studies to assess feasibility. Initial culture efforts centered on Bowden, St. Thomas in eastern Jamaica in an area that had high density of mangrove oyster, Crassostrea rhizophorae. There was previously a small, well-established traditional market for raw oysters in Kingston, the capital. The plan was to better service this market and to provide a new employment option. The initial technology was adapted from Cuban techniques (Wade et al. 1981). Naturally produced spat settle on the artificial rubber tyre cultch during the spawning season, and grown for eight weeks. Afterwards they are transferred to deeper water for a grow-out phase of 4-5 months on either racks or rafts. Culture was attempted at several coastal sites, but the most successful location has been on the east coast. There were few parasites and growth rates were relatively good. The industry has suffered from pollution and theft. A review of the methods, production and problems is provided by Richards (1992).